One of my oldest interests lies in systems that are able to self-propel, like animals or vehicles. Over the years, I have focused on three separate themes that fall under that broad umbrella: Hamiltonian Flocks, Self-Navigating Particles, and Force-Aligning Active Particles.

Force-aligning active particles – physics-Controlled robots

In recent years, I have collaborated with experimentalists in robophysics (in particular Matan Y. Ben Zion at Radboud University) to try and understand how physics can help design computationally cheap strategies to control large ensembles of robots.

In vibration robots (think of a toothbrush with a phone vibration motor on top), the response of a single robot to an external force contains a torque term, that re-aligns the polarity of the robot either towards or against the external force. The sign and speed of this re-orientation only depend on a single intrinsic quantity associated to the robot, that we called curvity as it has units of curvature and emerges from activity.

Noticing that this quantity has units of curvature leads to much simpler intuition about the system: if the sum of the curvity of a robot and of the curvature of an obstacle is negative, the robot will stick to the obstacle; otherwise they will collide and scatter away. The simplest test case is that of an incline: negative-curvity robots will rotate to go up them, while positive-curvity ones will go down them (videos courtesy of M.Y. Ben Zion).

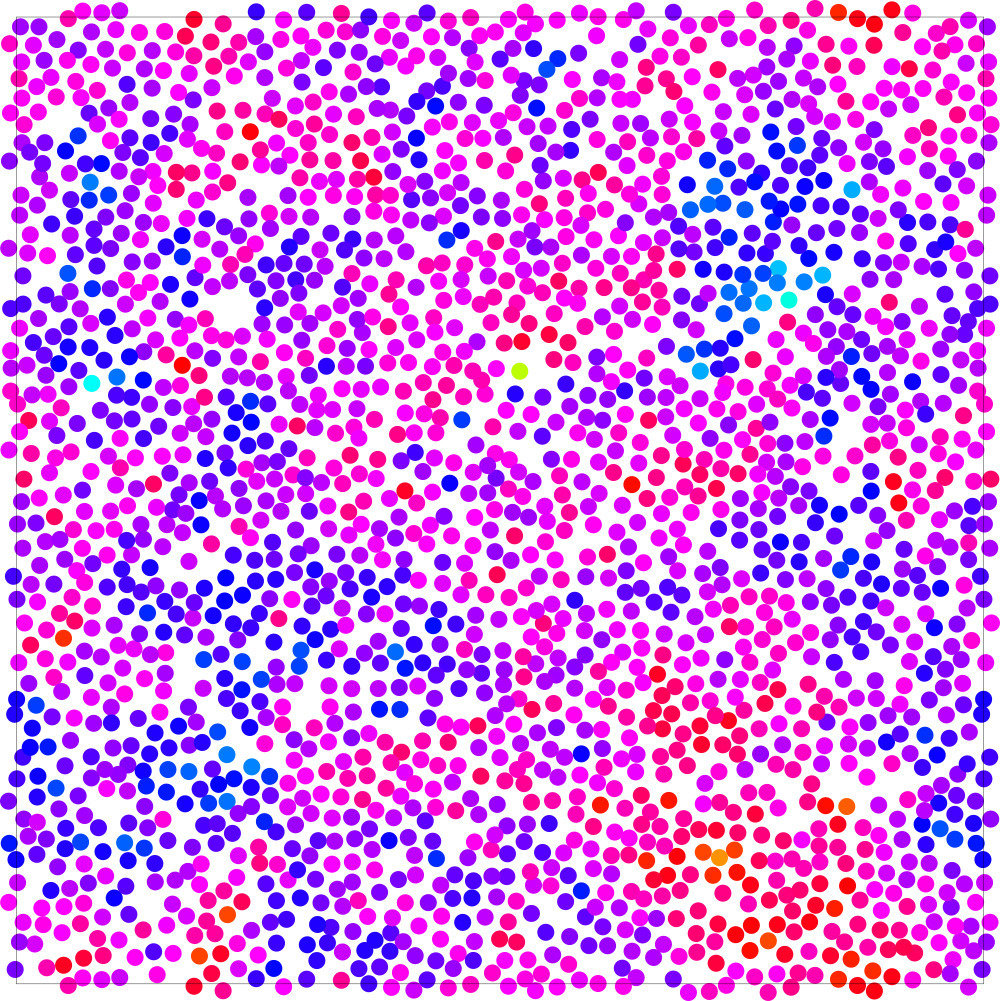

We showed that this simple geometric criterion for stickiness is also valid for assemblies of robots bumping into each other: in particular, the value of curvity fully determines, at a finite density and in the presence of noise in the dynamics, whether a group of robots will flock together, be disordered like a standard active gas, or cluster together.

Finally, we showed that the clusters formed due to curvity are not simply a modified Motility-Induced Phase Separation (MIPS) but an independent phenomenon and that, in particular, they are size-limited to saturate the stickiness criterion given above.

In other words, by controlling the curvity of a group of robots, we may control by mechanical means whether they flock together, flow, or form clusters, and in that last case control the size of clusters. This is a powerful non-computational control path that could be achieved by shifting either the center of mass or the contact points of robot dynamically.

Future directions include a better understanding of the interaction of such robots with obstacles with shifting curvature, as well as understanding the effect of polydispersity in the parameters of the robots.

See also: our paper on the matter, out in PNAS.

Self-navigating particles: jams and sync of stubborn pedestrians

In most systems of self-propelled particles, theoreticians consider particles that self-propel without a clear goal: they go West for some time determined by a persistence length and a self-propulsion speed, then turn North just because of fluctuations. However, in many animal and human systems, self-propelled agents instead have clear destinations. You, for instance, likely often self-propel to a specific restaurant where you have plans, or back home.

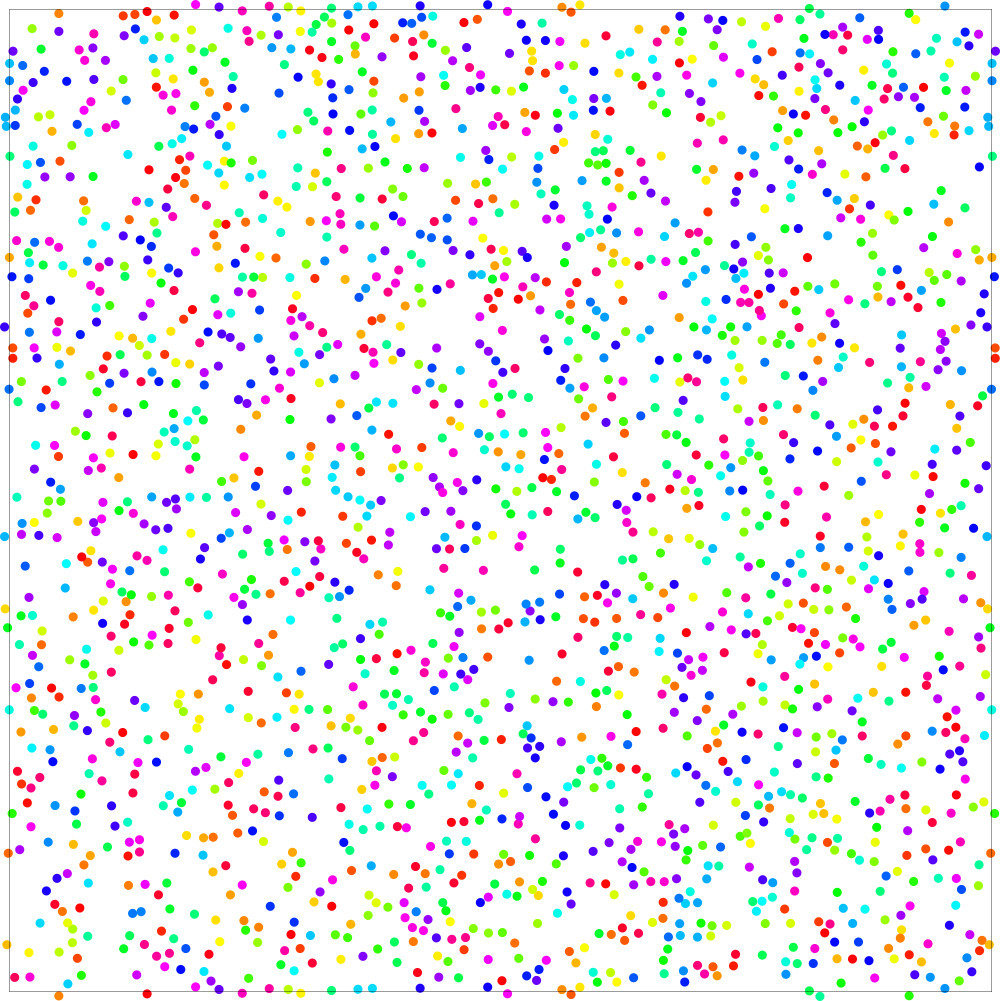

To model the dynamics of such systems that self-propel with a destination they want to reach, I and co-workers (Daniel Hexner and Dov Levine) introduced Self-Navigating Particles, particles that self-propel towards a particle-specific goal (particle 1 has its fixed home and particle 2 its restaurant it wants to reach) with some finite relaxation time to re-orient self-propulsion after interactions with the environment sends it astray.

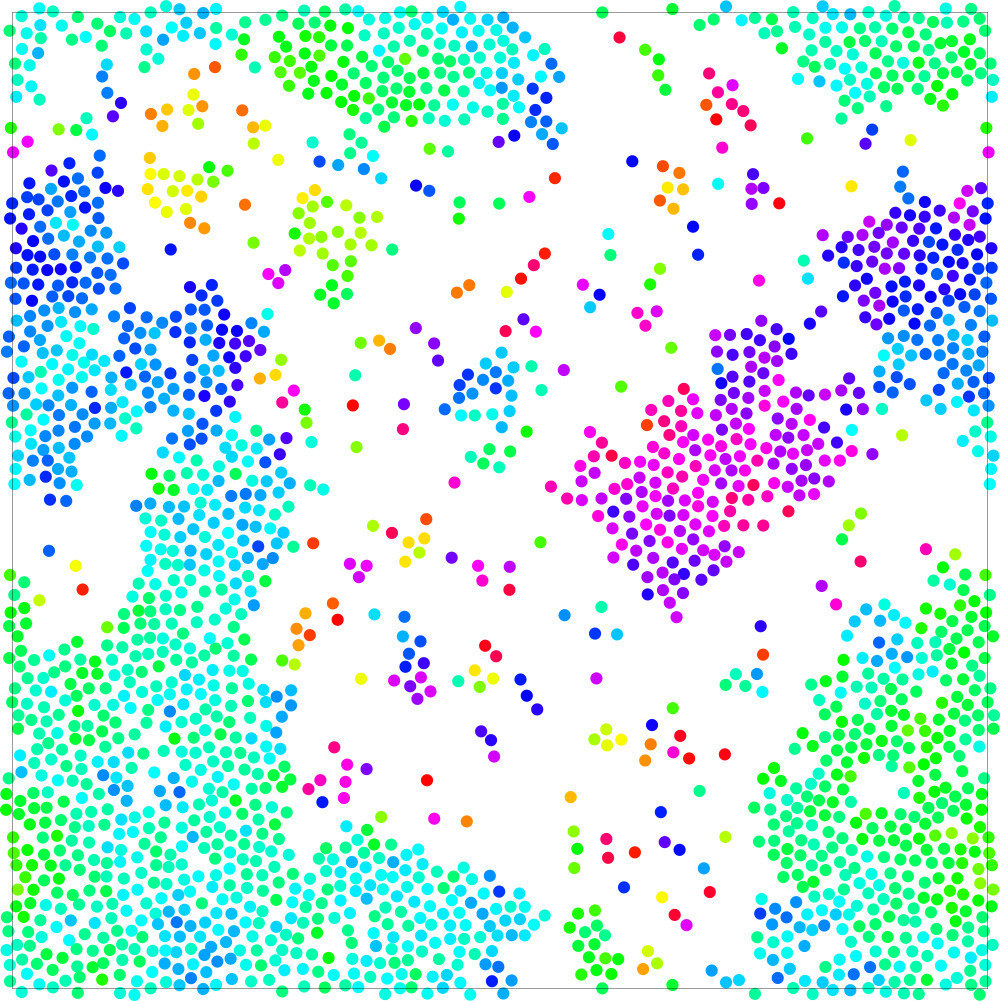

We showed that such systems displayed very violent absorbing-state transitions between circulating liquids and arrested traffic jams. These traffic jams occur because, as density grows, particles start clustering due to Motility-Induced Phase Separation (MIPS), which is then amplified due to the co-accumulation of destinations and particles in the same region of space. As such, MIPS plays the role of a precursor for much slower traffic jams in systems of self-navigating particles.

To alleviate this problem, one may simply add noise to the dynamics. This noise eventually melts the arrested traffic jams. Interestingly, at any given density above the MIPS threshold, the time particles take to reach their destinations is minimal close to melting, where particles may travel ballistically to their destinations in spite of collisions due to finite densities. At high noise intensities though, travel times systematically become diffusive, even at the single-particle level.

At finite noises, we also uncovered that such particles may display system-scale synchronization along circular orbits and flocking, in spite of the complete absence of either confining potentials or aligning interactions.

We showed that these observations can be understood through the emergence of stable circular orbits in the dynamics, and of effective interactions that span the radius of that orbit. As a result, when the size of orbits becomes comparable to the size of the system, it behaves like a mean-field ferromagnetic model for all particles that follow orbits with the same chirality. It thus follows that particles spontaneously form 2 chiral groups of synchronized particles. To resolve collisions in the best way possible, the particles then form lanes of equal chirality, such that the steady state is a mesmerizing ballet of particles that interact as little as possible.

Future directions include understanding which minimal interactions could avoid traffic jams in these systems, so as to provide cheap solutions for multi-agent pathfinding.

The work on traffic jams as well as that on synchronization can both be found in PRE.

HAMILTONIAN FLOCKS: COLLECTIVE MOTION WITHOUT ACTIVITY

Collective motion is considered a signature property of active matter, as it is commonly observed in living and artificial systems of self-propelled particles. However, it is not completely obvious a priori that only non-equilibrium systems may display collective motion. Indeed, a common assumption when claiming the contrary is that models to consider should display Galilean invariance, i.e. be invariant up to a trivial shift of kinetic energy under a translation of all velocities by a constant value.

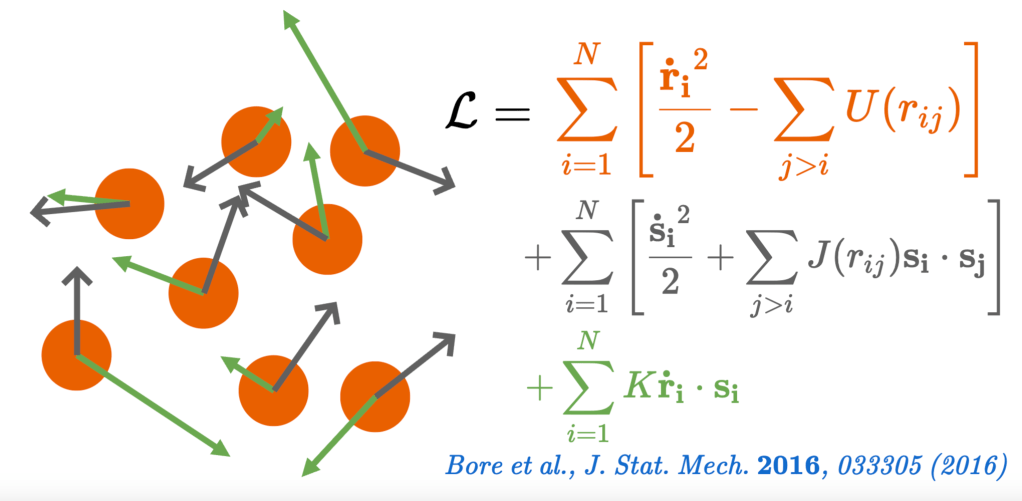

However, one may define perfectly well-behaved statistical mechanics for a non-Galilean liquid in which the velocity of each particle is linearly coupled to an internal polarity. I thus worked on a minimal model that may be expected to display a spontaneous transition to collective motion in the energy-momentum or temperature-momentum ensemble. This model contained 3 key ingredients: pair repulsion between particles, pair alignment between polarities, and a linear polarity-velocity coupling in the Lagrangian formalism.

I first showed that the interplay of repulsion and alignment generically leads to a ferromagnetism-induced phase separation between a ferrofluid and an isotropic gas, where the Curie line plays the role of the gas-side spinodal below a critical point. In the special case of 2d geometry, I also showed that the interplay of attractorepulsion and alignment made the magnetization transition more subtle than the standard BKT scenario for XY spins on a lattice.

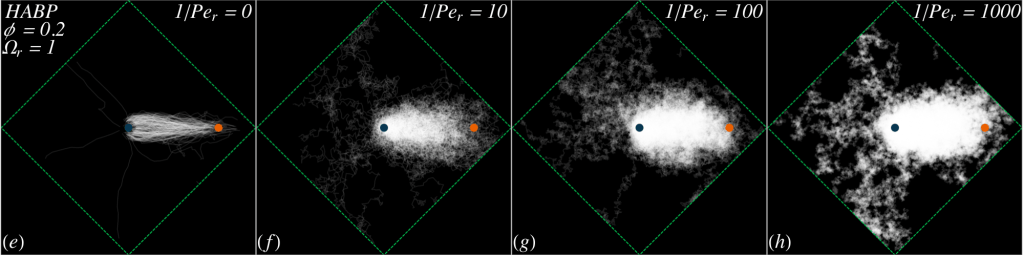

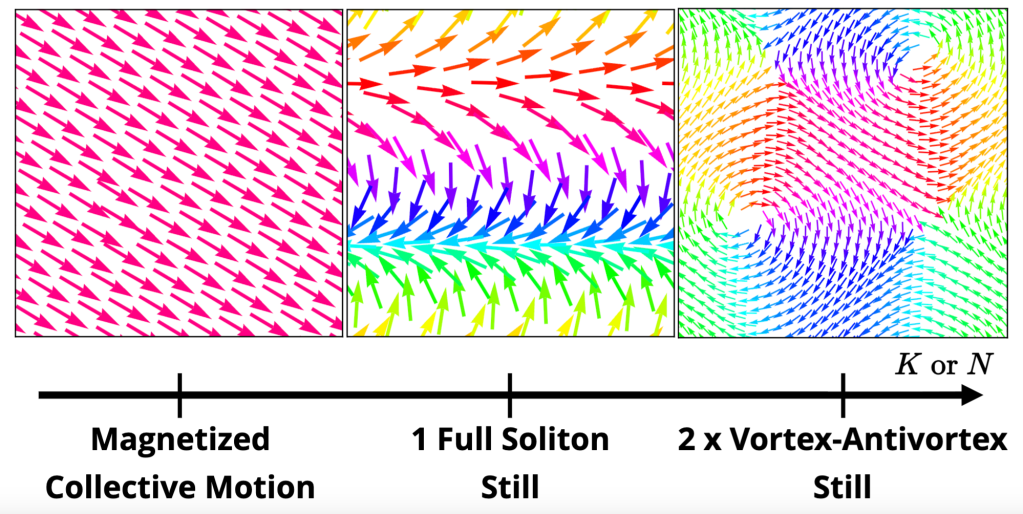

I then showed that the spin-velocity coupling did indeed lead to a spontaneous formation of collective motion, as long as the spin-velocity constant was small enough that the total kinetic energy cost was cheap enough compared to the magnetic energy gain due to alignment. The low-temperature/low-energy phases are then typically polar and collectively moving. When kinetic energy becomes too costly, the system forms the least costly magnetic texture with zero total magnetization to avoid having to move collectively, so that phases with only 2 vortex-antivortex pairs are typically observed. Interestingly, collectively moving phases also form at finite temperatures in cases in which the ground state is non-magnetic, a situation reminiscent of order by disorder in frustrated magnetism.

Finally, focusing on the case of the phase-separated collectively moving regime, I showed that such a conservative system could form “Hamiltonian flocks”, droplets of dense particles that collectively move in a dilute background gas. These flocks display dynamics well described by active-Brownian-like ones, but with inertia on the angular velocity resulting in transient superballistic angular dynamics, that I coined “Angular Velocity Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Particles” (AVOUPs), an unusual but active-like dynamical behaviour that is surprising in an overall conservative system. These flocks also display velocity and speed correlations strikingly similar to those of real flocks, highlighting that the latter may actually have much simpler causes than anticipated.

All in all, this line of work shows that many surprising features emerge in equilibrium settings if one simply relaxes the Galilean invariance of the system in just the right way. Thus, more work should focus on disentangling the roles of Galilean symmetry breaking and of activity per se in the properties of active models of particles.

Future directions on this work involve understanding how Galilean invariance and time-reversal symmetry are linked in such counter-intuitive systems that admit a Gibbsian distribution, yet allows flows, so as to better understand the relative roles of activity and of the Galilean symmetry breaking in active matter.

This work was so far published as three papers, one on FIPS in JCP, one on the phases of the non-Galilean model at large densities in J. Stat. Mech., and one on Hamiltonian flocks and their dynamics in PRL.