Take a bunch of sand grains, pour them into a jar, tap them, and you will get a jammed packing of sand grains, an ensemble of (mostly) repulsive particles that develop an emergent rigidity because of the structure of their contacts. Understanding the diversity and commonalities of jammed packings is one of the longest-standing problems in statistical physics.

In my work, I have focused on two particular aspects of the problem: developing tools to understand the structure of the energy landscape of high-dimensional complex systems, and designing simple models to capture general trends in the behavior of jammed packings.

The energy landscape view of jamming – and beyond

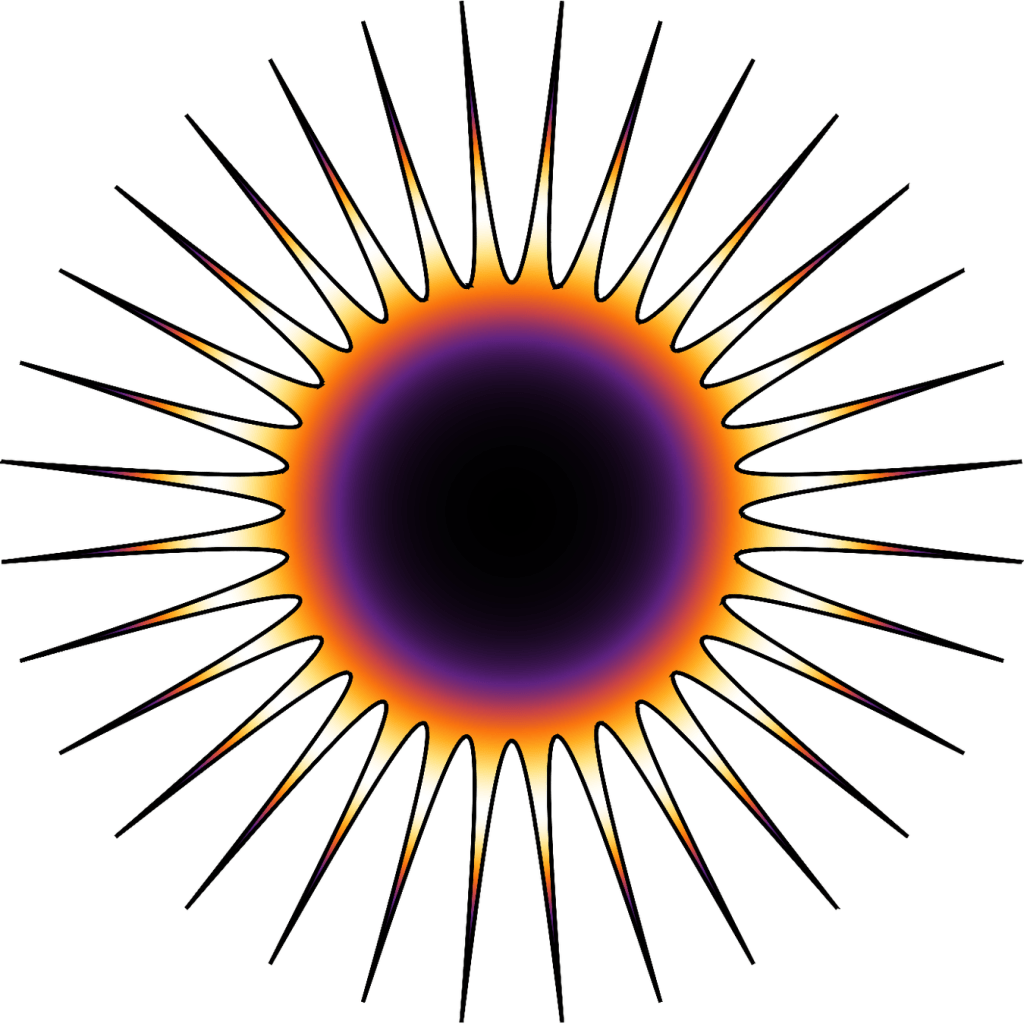

Jamming can be studied in the computationally simpler simpler case of soft-sphere packings, i.e. dense assemblies of particles that repel each other with potentials that are finite at all finite distances, and fall to zero at a finite range. Such models were for instance proposed to capture qualitative properties of foams and emulsions. In that context, the system can be studied via its energy landscape, meaning that instead of considering the system as made of N particles living in d dimensions, one may consider it as a single particle evolving on an Nd-dimensional energy function, the minima of which control low-temperature physics.

In polydisperse soft spheres, there is a combinatorially large number of non-equivalent minima in the landscape, it is thus unreasonable to hope studying them all extensively. One must instead develop sampling strategies, where measurements on a large but non-extensive number of minima are performed, to extract meaningful information. In particular, it is meaningful to study the basin of attraction of each minimum, the region that converges to that particular minimum when following the path of steepest descent. Indeed, the volume of each basin indicates the relative probability of finding the associated minimum by an instantaneous quench to zero temperature, and the geometry of basins determine relaxation paths through the landscape.

This is challenging, as basins of attraction are intricate high-dimensional shapes defined by a differential equation that is numerically costly to solve accurately in high dimensions.

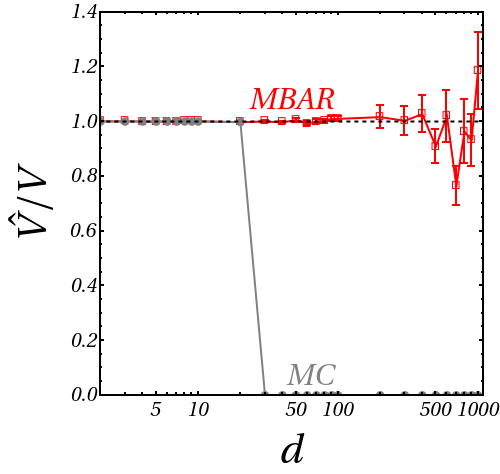

On the geometric side, I have built upon past work by Daan Frenkel’s group to produce a benchmark of a Frenkel-Ladd-type Replica-Exchange Markov-chain Monte Carlo scheme to measure the volumes of high-dimensional shapes. I have shown that such methods remain usable in simple cases with known volumes up to thousands of dimensions, when naïve Monte Carlo methods fail after a few tens of dimensions.

To alleviate the computational cost of solving steepest descent in high dimensions, many past works have relied on optimizers rather than Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) solvers to study the geometry of energy landscapes. We have recently shown that this choice strongly altered the outcome of their computations, and proposed a viable ODE solver to study the problem in the example of jammed packings.

Contrary to past claims and popular wisdom, we show that the basins of attraction of soft sphere packings are smooth objects, not fractal ones. Furthermore, we show that the incorrect choice of methods biases every property imaginable in high dimensions, from the distribution of energies at minima to the apparent basin volumes, casting doubt on past quantitative works.

The implications of this work go way beyond jamming.

On the one hand, the energy picture has been used extensively to study not just physical systems, but also more generic optimization problems such as the training of neural networks on the loss landscape. Our work emphasizes that intuition on the landscape gained by fast optimization algorithms are likely wrong, and that many past claims may be dynamics-dependent.

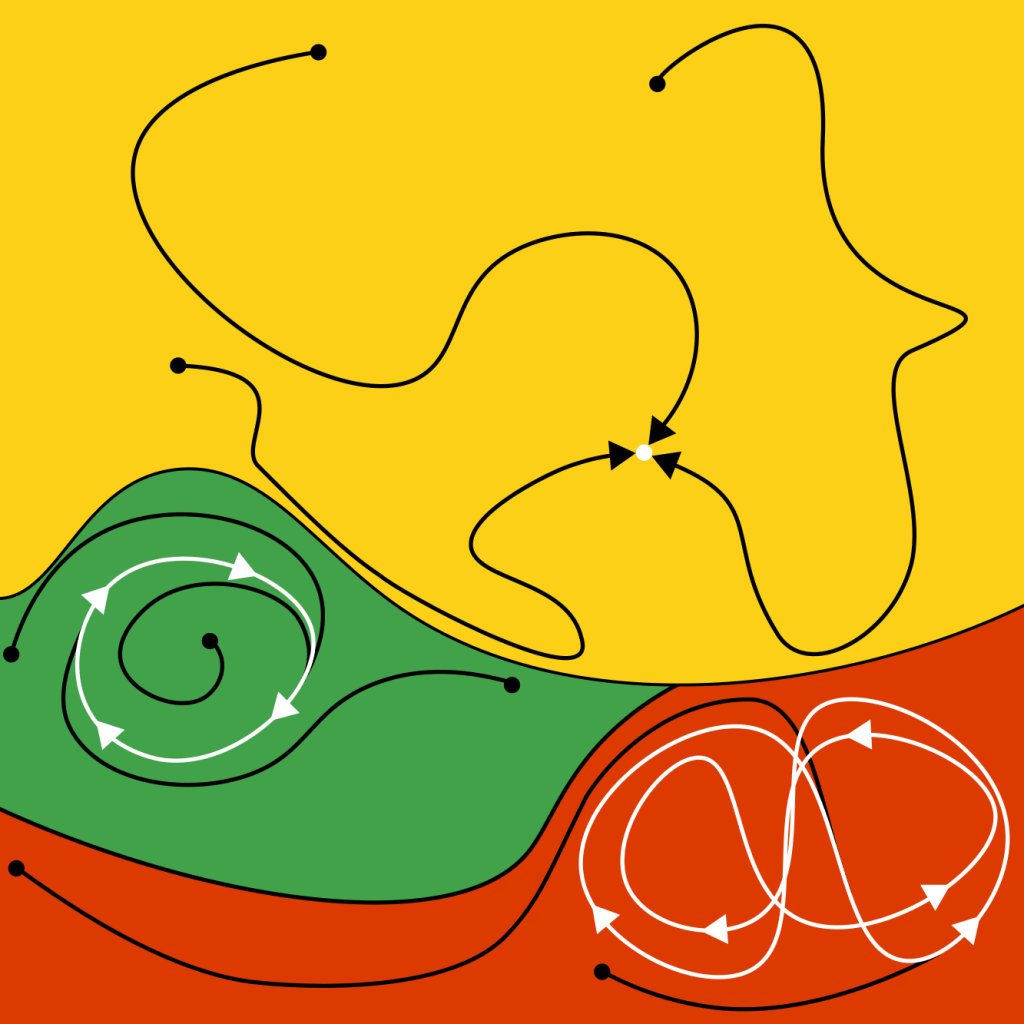

On the other hand, the study of basins of attraction is applicable to generic dynamical systems, not just gradient descent – bringing over tools from this line of work to purely dynamical systems like ecological dynamics will provide invaluable information on the complexity of their dynamics and the variety of their steady states.

This work has so far been published as part of a special issue on granular physics in Papers in Physics, and as a preprint that is currently under review as of September 2025.

EStimating the effect of polydispersity on the jamming density

Another direction to study jammed systems is to find simple laws that qualitatively capture average properties – a task that is made difficult by the inherent non-equilibrium properties of the systems of interest, as they are either athermal like sandpiles or quenched to low temperatures too fast to be equilibrated.

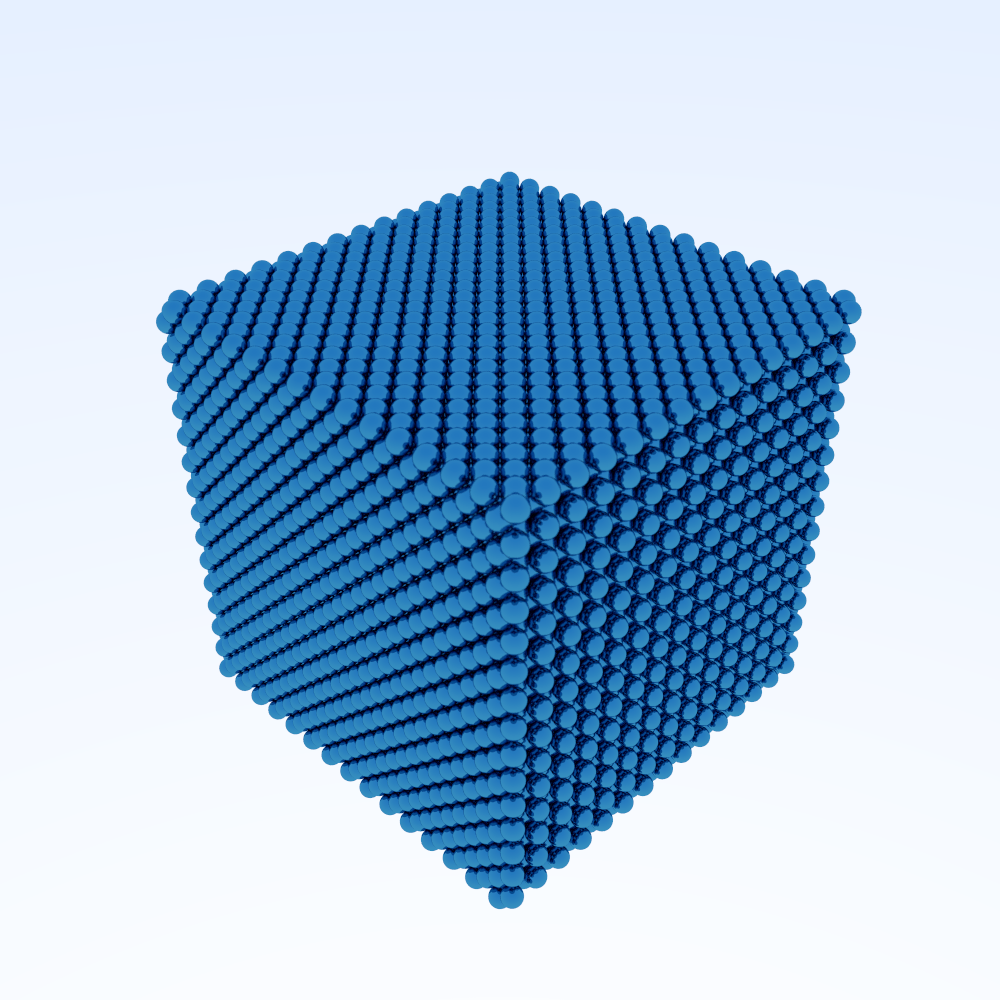

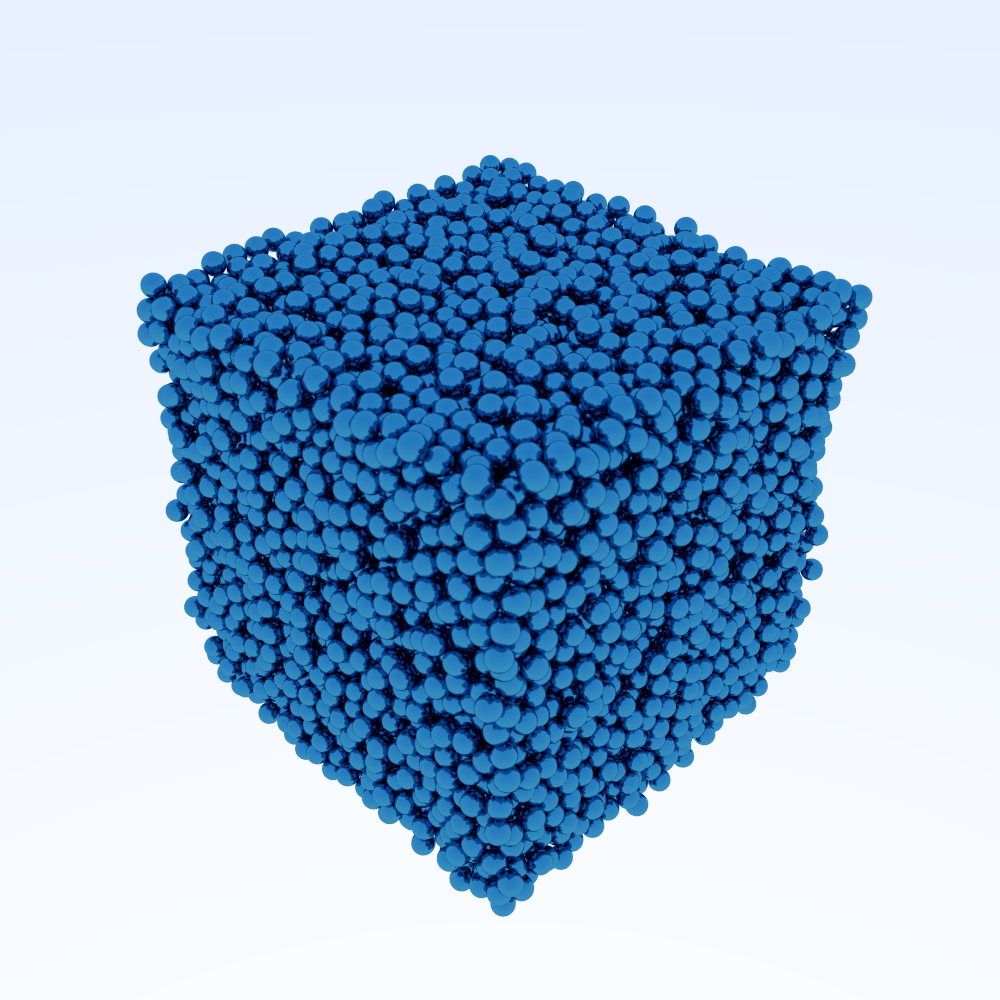

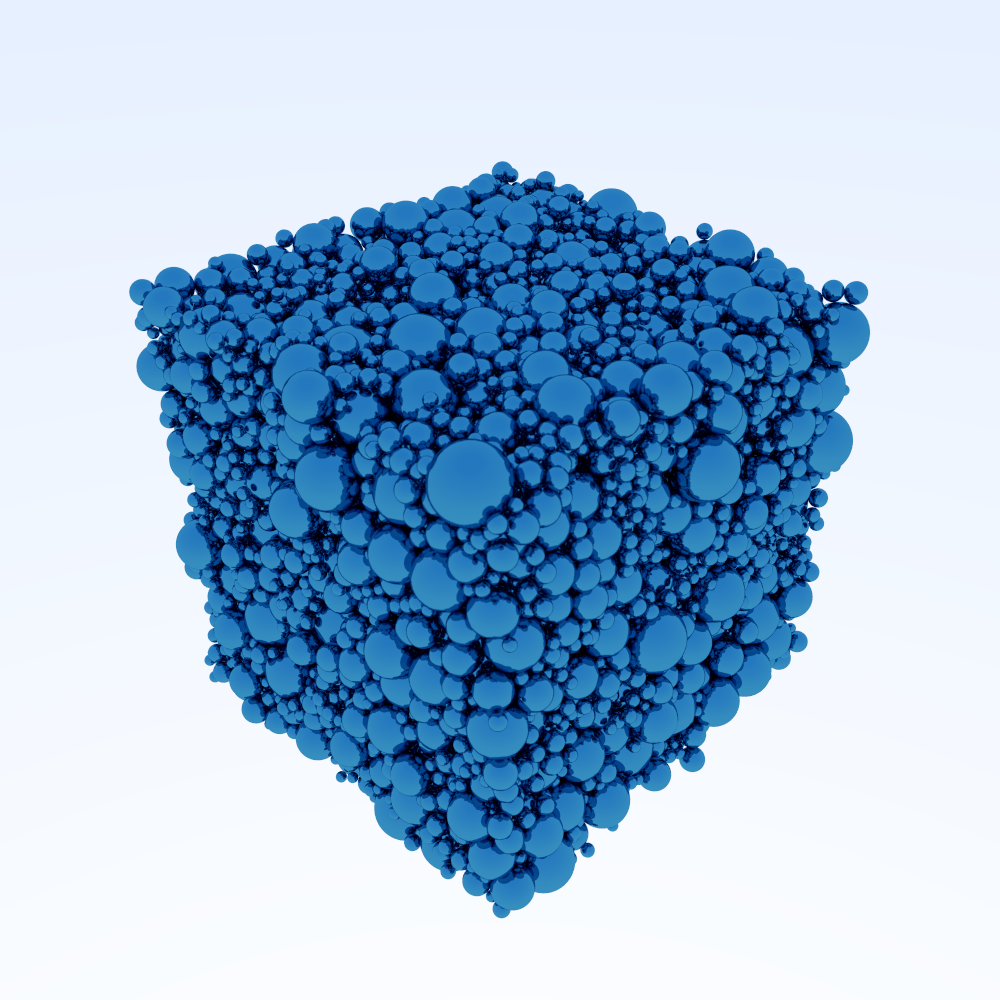

As a simple minimal target, consider the effect of polydispersity on the packing fraction of disordered systems. Even in the case of monodisperse particle size, sphere packings are the matter of many works and debates, in particular on the existence and nature of non-crystalline packings.

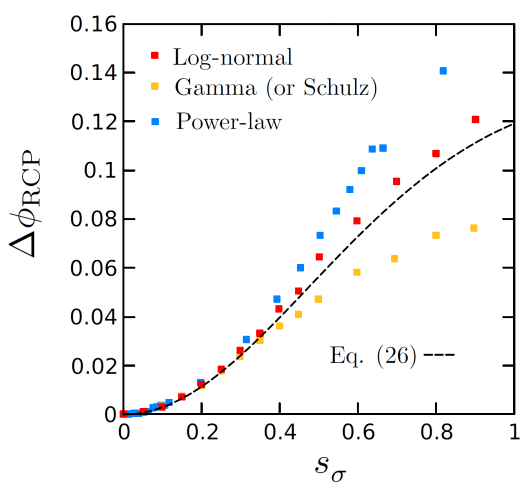

In my work, I have shown that one may qualitatively approximate the branch of lowest-coordinated jammed packings by an equilibrium-inspired equation that relies on an equation of state to predict crowding as a function of filling fraction. In particular, the point at which this branch hits the isostatic line (number of contacts per sphere equal to 2d with d the dimensionality of space) yields a prediction for the densest isostatic packing, a well-defined special packing.

Relying on the fact that this model works reasonably well in monodisperse packings, we extended it to polydisperse ones, by relying on polydisperse equilibrium equations of states rather than monodisperse ones. We showed that it captures the evolution of numerically measured densest isostatic packings shockingly well in 3d, across kinds of polydispersity.

This line of work shows how defining slightly different objects in the ensemble of jammed packings, for instance the densest isostatic packing, may lead to new predictions that may prove useful in practice.

This work has been published in JCP.